Svom detects one of the most distant bursts in the Universe and JWST observes the most distant supernova ever detected

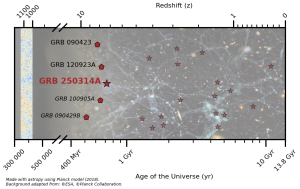

On March 14, 2025, the French-Chinese satellite SVOM (Space-based multi-band astronomical Variable Objects Monitor) detected an exceptional gamma-ray burst, named GRB 250314A, originating from the outskirts of the Universe. As soon the ECLAIRs and GRM instruments triggered, the satellite slewed and positioned its narrow-field X-ray (MXT) and visible (VT) instruments to observe this source, which—thanks to joint observations from several observatories and satellites, including JWST—turned out to be one of the most distant bursts ever recorded. GRB 250314A is a long gamma-ray burst, produced by the explosion of a star when the Universe was only 730 million years old, and whose light traveled nearly 13 billion years before being detected by our instruments. 110 days after SVOM discovery, JWST targeted the galaxy hosting this burst. Early photometric analyses suggest that it may be associated with a supernova resulting from the violent gravitational collapse of a massive star at the end of its life, closely resembling local supernovae of the same type. This result may indicate a surprising continuity in the explosion processes of massive stars (>20 solar masses), from the early Universe to the present day.

A flawless sequence

At 12:56 UTC, the SVOM ECLAIRs alert instrument detects a signal coming from the depths of the Universe and immediately issues an alert— the countdown begins. The operation starts immediately : the satellite reorients itself to observe the relevant region of the sky with its narrow-field MXT and VT instruments.

At 13:07 UTC, the Chinese GRM instrument confirms the detection.

At 13:23 UTC, the teams decide to send out a circular to alert the entire community.

The community on alert

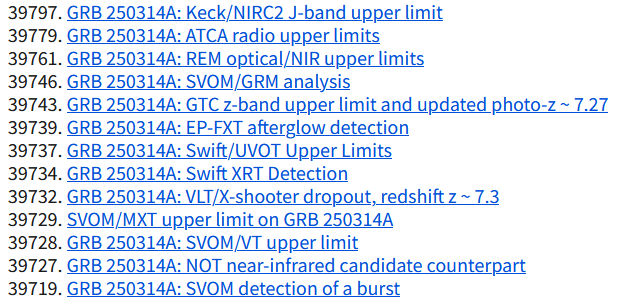

Thanks to the alert transmitted by the burst advocates, other observatories step in to search for X-ray, optical, and infrared counterparts.

The Neil Gehrels Swift space observatory and the Einstein Probe satellite point their instruments toward the source. An X-ray counterpart is localized by the X-ray detector on board Swift. The Nordic Optical Telescope (NOT) discovers the near-infrared counterpart within the error box provided by Swift. Observations from Einstein Probe even confirm the transient nature of the X-ray counterpart— a key clue supporting the presence of a GRB afterglow.

On the SVOM side, however, the MXT and VT instruments did not detect a counterpart — an absence that may indicate that the event is particularly distant or heavily absorbed by surrounding gas and dust.

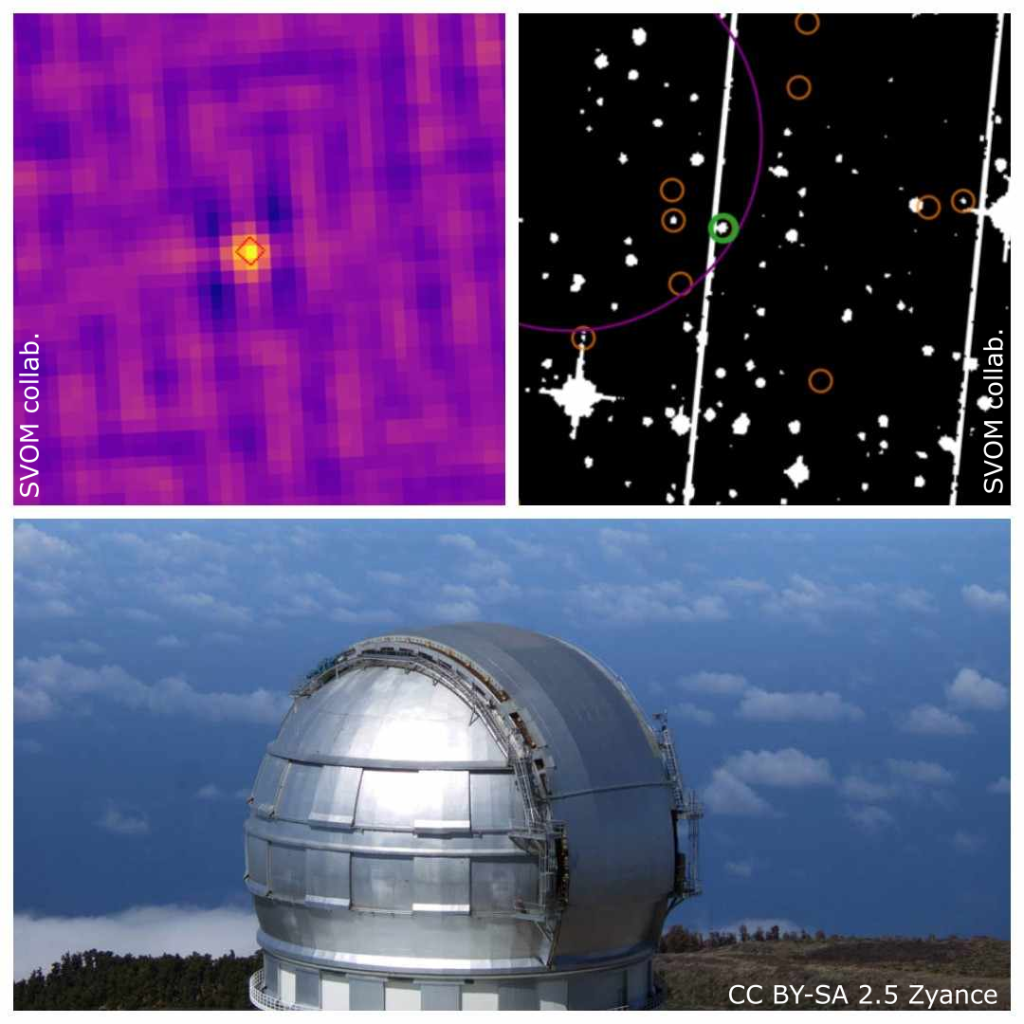

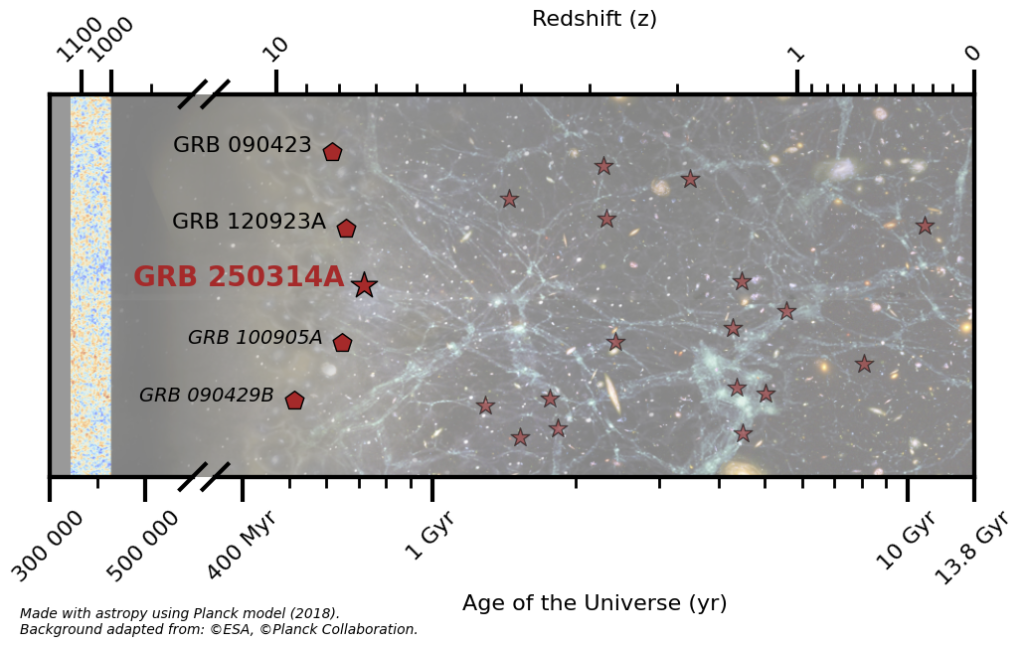

17 hours after the alert, using the precise position provided by NOT, the Very Large Telescope (VLT) equipped with its X-shooter spectrograph begins its observation. Very quickly, the observed optical/infrared spectrum shows a spectral shift corresponding to a redshift (z) of about 7.3. This measurement is then supported by photometric observations from the Gran Telescopio Canarias. GRB 250314A ultimately turns out to be the fifth most distant GRB ever identified. The previous GRB at such a high redshift (z > 7) had been identified roughly twelve years earlier!

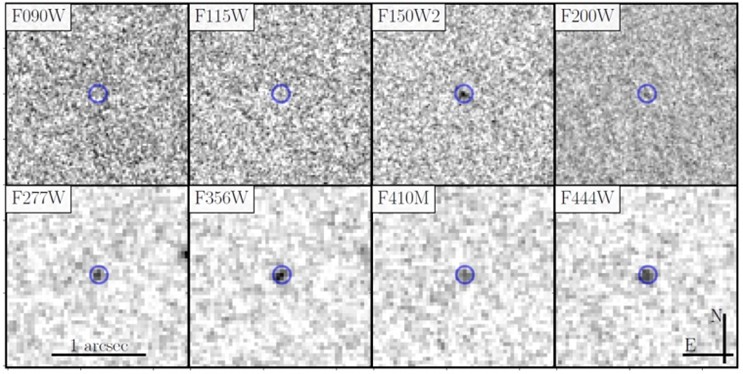

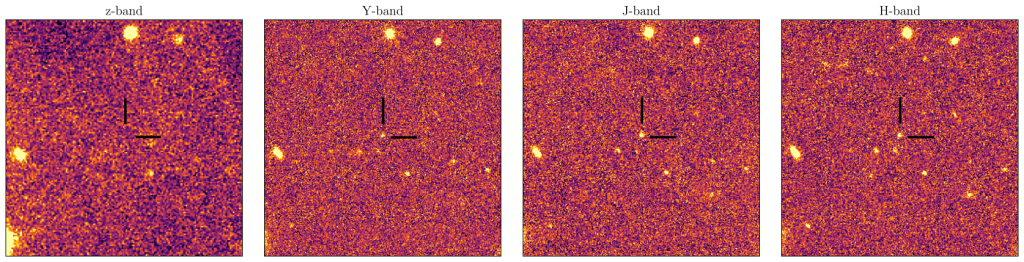

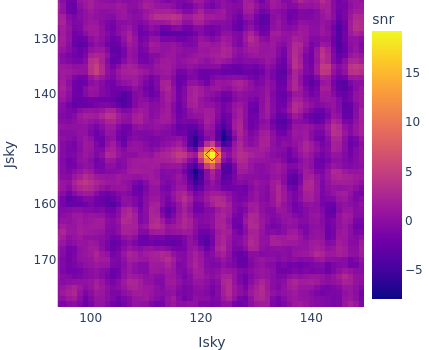

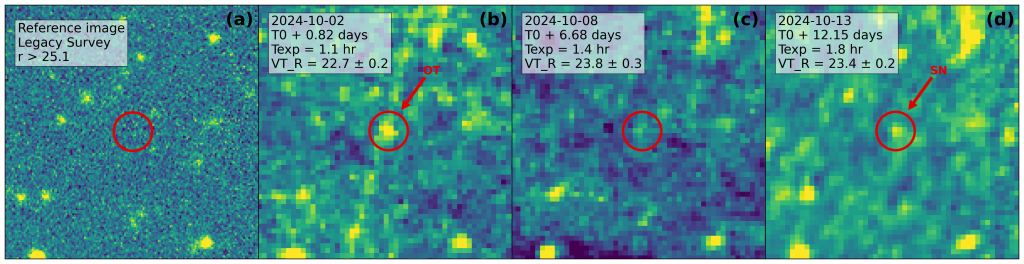

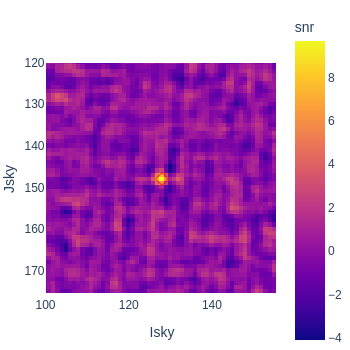

110 days later, the JWST satellite observes the burst position and, using its NIRCam instrument, detects an infrared emission. In the JWST images, the emission seen in the reddest filters is interpreted as the combination of the GRB host galaxy and the emergence of the associated supernova. An additional observation, already scheduled in nine months, should confirm the disappearance of the supernova.

A possible homogeneity of supernovae since the dawn of the Universe?

The photometric observations carried out by the JWST on the field of GRB 250314A demonstrate the satellite ability to observe traces of extremely distant stellar explosions. These early results show a strong correspondence with the well-known model of supernova SN 1998bw, associated with a nearby gamma-ray burst (z = 0.0085), GRB 980425. Beyond the fact that SVOM has enabled the observation of the most distant supernova ever detected (by far), this discovery suggests that the collapse mechanism of massive stars (the interpretation for the origin of long gamma-ray bursts) may be the same in the early Universe as in our local Universe, very close to us in both distance and time.

The supernova associated with GRB250314A is by far the most distant supernova ever detected. The following table provides a comparison of the most distant supernovae detected to date, with their respective redshifts.

| Event | Redshift |

Age of the Univers at explosion time (Gyr) |

Light travel time (Gyr) |

Comoving distance (Glyr) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GRB 250314A | 7,3 | 0,73 | 13,0 | 28,5 |

| SN 1000+0216 | 3,899 | 1,6 | 12,1 | 25,6 |

| DES16C2nm | 2,0 | 3,3 | 10,5 | 16,4 |

| SN UDS10Wil | 1,914 | 3,5 | 10,3 | 16,0 |

| SN SCP-0401 | 1,71 | 4,0 | 9,9 | 14,7 |

SVOM article : SVOM GRB 250314A at z ≃ 7.3: an exploding star in the era of reionization

JWST article : JWST reveals a supernova following a gamma-ray burst at z ≃ 7.3

The news in video by Andrea Saccardi (in French)

Contact: Andrea Saccardi

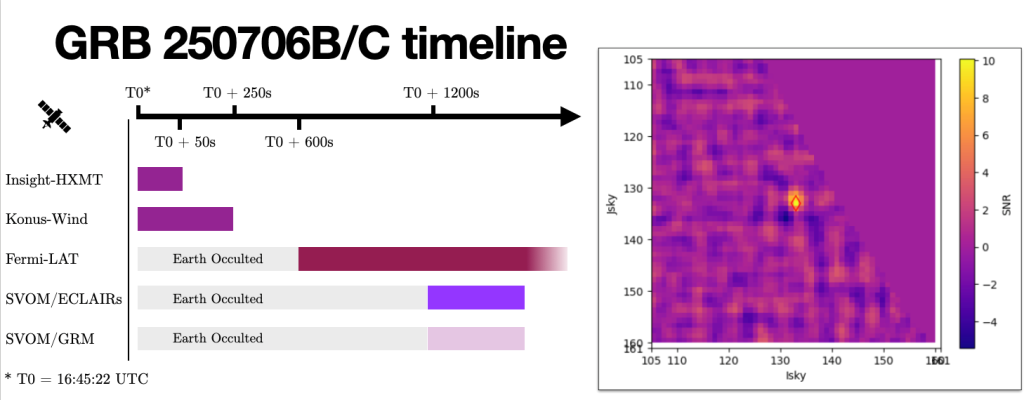

GRB 250706B: an “afterglow”-rise caught from space

On July 6, 2025, the Universe staged an impressive display. At 16:45:22 UTC, the Konus-WIND spacecraft was startled by a powerful 40-second flash of gamma rays, later catalogued as GRB 250706B. While this Gamma-Ray Burst (GRB) was impressive by its initial prompt brightness, it would be its afterglow that would steal the show.

Ten minutes after the initial blast, the fading light of the burst’s afterglow appeared above the Earth’s horizon and into the field of view of the LAT instrument onboard the Fermi satellite, which recorded photons carrying energies as high as 21 billion electronvolts. Then, another 10 minutes later at 17:06:04 UTC, as the burst emerged from behind the Earth for SVOM, its ECLAIRs instrument was triggered — not by the initial flash of prompt emission photons as is usually the case, but by the bright X-ray afterglow itself. This was the first time ECLAIRs had triggered on a GRB afterglow which was made possible thanks to its special image trigger mode and its lower energy threshold of 4 keV.

SVOM swiftly reacted, slewing toward the source in less than three minutes. Its onboard telescopes, MXT and VT, captured the afterglow pinning down the position of the burst to within a fraction of an arcsecond, enabling the X-shooter instrument installed at the Very Large Telescope in Chile to measure its redshift at z = 0.942, equivalent to a distance of 6.3 billion parsecs away, from a time when the universe was barely half its current age.

Finally, one month later on August 5th, after the afterglow finally faded, the NIRSpec instrument of the James Webb Space Telescope revealed the unmistakable signature of a broad-lined Type Ic supernova at the same location — the telltale mark of a massive star’s core collapse, confirming the collapsar origin of GRB 250706B. The wealth and quality of data collected on this event should allow scientists to get a detailed understanding of the physics at play and attempt to provide answers as to why it was so bright.

GRB 250706B was more than just another detection. It was a rare “afterglow”-rise: a cosmic sunrise, as the light of a cataclysm long past crested the Earth’s edge into our instruments’ view. If a human with X-ray vision had been onboard the SVOM satellite, they too would have witnessed an extraordinary sight — not the familiar golden glow of dawn, but the sudden rising of a distant afterglow, born in the violent death of a star billions of years ago.

Contact: Jesse Palmerio

Happy Birthday, SVOM!

22 June 2025 marks the first anniversary of the SVOM satellite in orbit. One year ago, the satellite was launched from the Xichang base in China at 07:00 UTC. Following the launch, the subsequent phases took place:

- in-orbit commissioning phase from late June to late September 2024: commissioning of all platform functions and gradual activation of the instruments;

- validation phase from October 2024 to mid-January 2025: adjustment of system parameters, instruments, and scientific calibration;

- from mid-January 2025 onwards: start of the scientific operations phase.

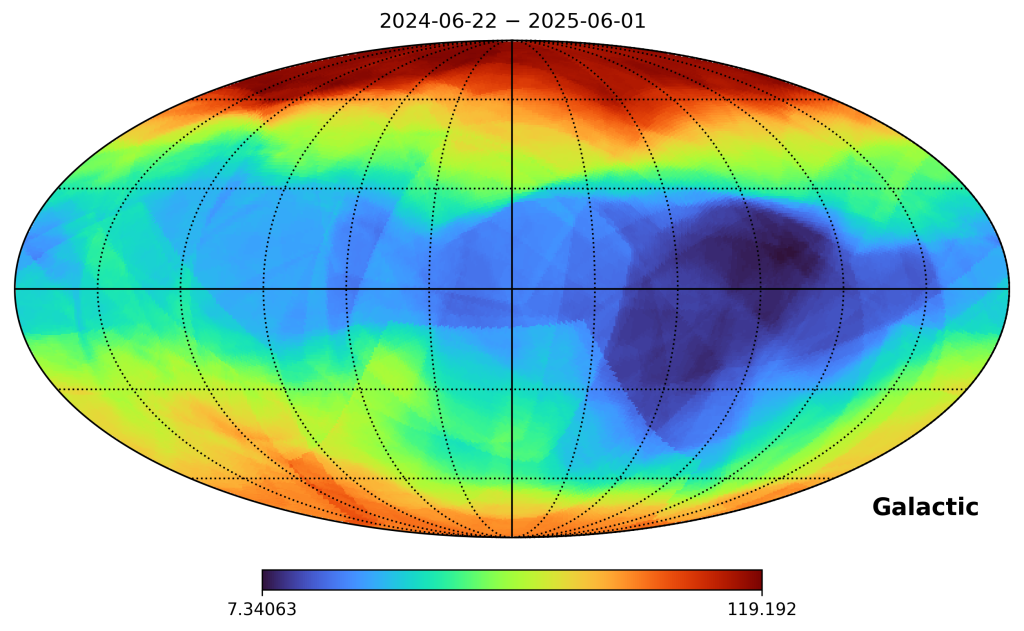

The map below shows the exposure time of different regions of the sky (in galactic coordinates) during this first year for the ECLAIRs telescope. The most exposed regions are the galactic poles, in line with the planned SVOM attitude law.

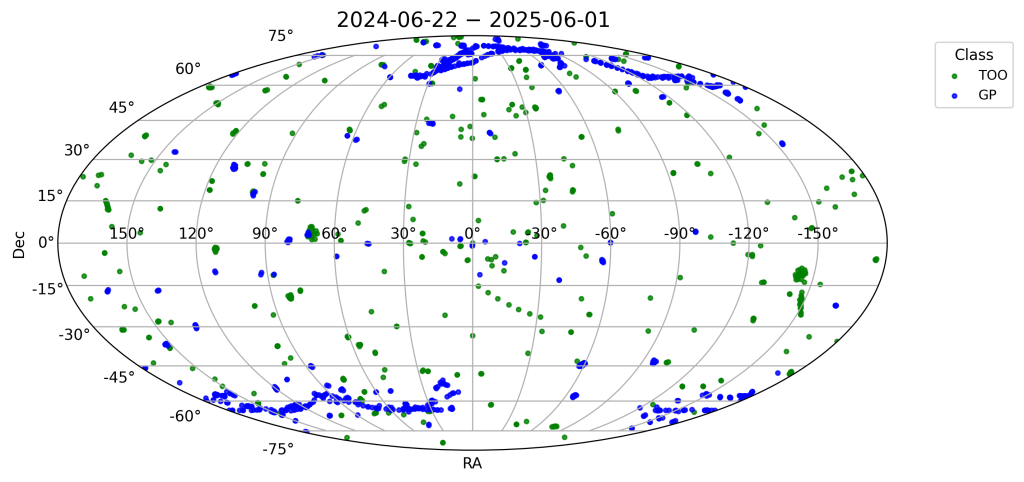

The map below shows the pointing directions of the platform during this first year (in galactic coordinates). The colours indicate the nature of the pointings:

- in blue: general programme pointings, observing predefined areas of the sky while awaiting potential gamma-ray bursts;

- in green: target of opportunity pointings, observing known astrophysically interesting targets.

In total, SVOM devoted 35% of its available time to observing targets of opportunity, with half of that time spent revisiting gamma-ray bursts to build their visible light curves using the VT. Over two-thirds of these revisits were conducted for SVOM-detected bursts.

Thanks to the observing strategy applied this first year, SVOM successfully detected and observed 132 bursts, including:

- 111 detected by GRM;

- 47 detected and localised by ECLAIRs;

- and among these, 89 were also detected by other missions (Einstein Probe, Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory, Fermi).

Thanks to the responsiveness of the SVOM system and its teams, and the excellent multi-wavelength follow-up from our partners, around fifty gamma-ray bursts were observed in soft X-rays, about thirty in visible light, and redshift was successfully measured for 26 events. In particular this year:

- ECLAIRs detected its first burst on 13 July 2024;

- a very particular burst rich in soft X-rays was detected on 1 October 2024 and observed by the James Webb Space Telescope;

- the burst detected on 5 February 2025 is a perfect example of the SVOM system in action;

- a particularly distant burst was detected on 14 March 2025;

- GRB 250403A, proof of the phenomenal power of gamma-ray bursts;

- SVOM teams were honoured and awarded during China’s “Space Day” on 24 April 2025.

The results of this first year speak for themselves. Detections and observations by SVOM and its partners have generated over 900 scientific circulars. The next step is to continue fine-tuning the mission and instruments. Meanwhile, a series of scientific publications is being prepared to formally present these results to the scientific community.

Happy Birthday SVOM, and congratulations to all the teams!

GRB 250403A, proof of the phenomenal power of gamma-ray bursts.

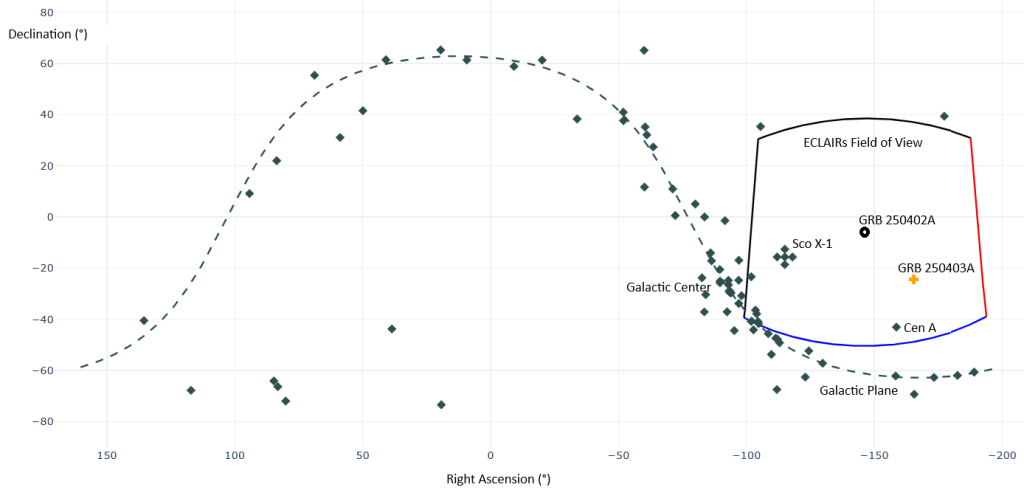

On 03 April 2025, at 09:42 UTC, SVOM was revisiting the gamma-ray burst detected the previous day, GRB 250402A. The optical axis of the instruments was pointing in the direction of the Virgo constellation (AD= 13.78° DEC= -5.94°).

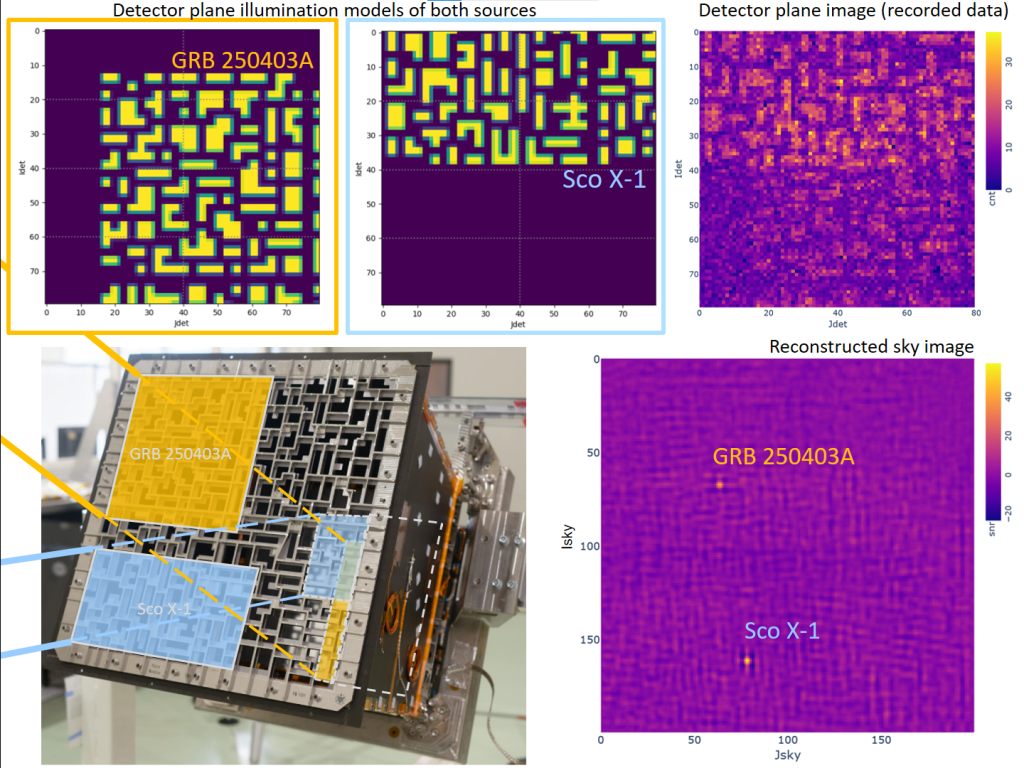

Since ECLAIRs has a field of view of 2 steradians (approximately 90 degrees by 90 degrees), several sources were present within it, including Scorpius X-1.

Scorpius X-1, abbreviated Sco X-1, is an X-ray source located in the constellation of Scorpius about 9,000 light-years from Earth. Apart from the Sun, it is the most powerful source of X-rays in the sky. It was discovered by chance in 1962 by a team led by Riccardo Giacconi, using a sounding rocket equipped with an X-ray detector. At that time, Riccardo Giacconi was looking to study X-ray emissions from the Moon. The discovery of this object marked the birth of X-ray astronomy. Riccardo Giacconi was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics 40 years later, in 2002.

Sco X-1 is likely to be a binary system hosting a neutron star that tears matter from its companion star, forming an accretion disc. The mass of the companion star is only 0.42 solar masses, hence the classification as a low-mass binary system.

In the ECLAIR energy range of 5 to 20 keV, Sco X-1 is therefore the brightest source in the sky. Normally we try to keep this source out of the field of view of ECLAIRS so as not to saturate its detectors. The presence of Sco X-1 in the ECLAIRs field of view disturbs the trigger and significantly reduces the sensitivity of the telescope.

On 03 April 2025, at 15:15 UTC, a flash appeared in the ECLAIRs data, GRB 250403A. This burst lasted around twenty seconds and triggered the SVOM machinery with the emission of a GRB alert, the drafting of a circular (GCN 40026) and the conduct of a ground follow-up campaign. This follow-up campaign resulted in an estimate of the distance of the burst by measuring its redshift. With a redshift equal to 1.847 (GCN 40162), this burst occurred when the universe was only 3.58 billion years old. The photons that reached our detectors travelled for 10.14 billion years.

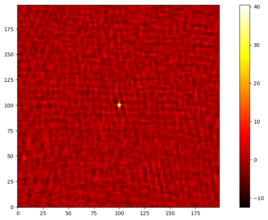

The image produced by ECLAIRs is very interesting and shows us the power involved in a gamma-ray burst. In Figure 2, at the moment of the flash, we can clearly distinguish the two mark patterns projected by Sco X-1 and GRB 250403A (for more information “play with ECLAIRs“). The two sources are also clearly visible in the deconvolved image with almost the same intensity, except that Sco X1 is in our galaxy and GRB 250403A is at cosmological distances…

Since the universe is expanding, using standard cosmological parameters, we can calculate the luminous distance of GRB 250304A, which is equal to 46.78 billion light-years. If we remember that the distance of Sco X1 is only 9000 light-years, then to impregnate our detector with the same intensity for 20 seconds, GRB 250403A was 26 million million times more intense than the brightest source in the sky in this energy range. That’s amazing !

GRB 250314A : A message from the depths of time

Just imagine. Around 13 billion years ago, one of the first stars in the Universe collapses into a black hole, releasing a flash of light of unprecedented power. This light travelled through the expanding Universe, past the first galaxies, then drifted through the ages… all the way to us. And on 14 March 2025, SVOM captured it.

A race against time

At 12:56pm UTC, a signal emerges from the depths of the Universe. ECLAIRs, SVOM’s watchful eye, detected it immediately and gave the alert. The machine is in motion: the satellite slews, points its small-field instruments MXT and VT, and begins to observe what could be one of the most distant gamma-ray bursts ever detected.

Thanks to the data transmitted in real time via the SVOM VHF network, our team of scientists on call are trying to determine whether this is a genuine alert or just a fluctuation in the background noise. The task is proving difficult for several reasons:

- At the time of the alert, the satellite was flying over a zone without coverage in the VHF network in the Pacific Ocean, preventing full reception of the data.

- The signal received by ECLAIRs was weak and below the detection threshold required to trigger an automatic alert to the international community.

At 1.07pm, we were truly alerted. Despite these difficulties, the simultaneous detection of the signal by the GRM instrument strengthened the scientists’ confidence. At 1.23pm, we decided to inform the international community by sending a brief message to observatories around the world.

A journey into the youth of our Universe

Thanks to the quick response of the SVOM scientists, other observatories quickly mobilised to search for the optical and near-infrared counterpart of the gamma-ray burst. The Nordic Optical Telescope, as well as the Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory and the Einstein Probe satellite, pointed their instruments at the source and pinpointed its location. Einstein Probe’s observations even confirm the transient nature of the optical counterpart, a key clue in favour of a gamma-ray burst. On the SVOM side, however, the MXT and VT instruments did not detect the counterpart. This could indicate that the event is particularly distant…

Excitement rises when, on the ground, the Very Large Telescope (VLT) and its X-shooter spectrograph take us back to the youth of the Universe. Around 17 hours after the SVOM alert, the spectrum acquired by the VLT revealed a spectral shift estimated at z ~7.3. The measurement was then confirmed by the Gran Telescopio Canarias.

Such a spectral shift means that the light from this gamma-ray burst was emitted when the Universe was only 730 million years old, compared with 13.7 billion years old today. This gamma-ray burst could well be a sign that one of the very first stars in the Universe has evolved into a black hole. It is the fifth most distant gamma-ray burst ever detected! As with the GRB 090423 and GRB 120923A bursts, the redshift of our 14 March burst was determined from its spectrum. For GRB 090429B and GRB 100905A, on the other hand, it was estimated without spectral measurement, by comparing the intensity through different filters. This method, which determines a photometric redshift, is less accurate than the spectroscopic method. Taking this into account, our gamma-ray burst is even the third most distant whose distance has been accurately measured using its spectrum.

Analyses of the data collected by SVOM and its partners will make it possible to establish the physical properties of this primordial burst and its local environment, in order to compare them with the populations of bursts detected throughout the different ages of the Universe.

A great night for hunting gamma-ray bursts

The burst advocate’s diary …

On Wednesday 5 February 2025, it was 10.25pm when I received a notification on my phone. The ECLAIRs telescope on board the SVOM satellite had detected a burst of X-rays and gamma rays and immediately triggered the satellite’s automatic re-pointing to observe the region of sky with the MXT and VT small field of view instruments.

We very quickly organised an emergency videoconference with the other scientists on call, during which we interpreted the first data sent in real time by the satellite via the VHF antenna network. This data, which includes a portion of the image of the sky acquired by the ECLAIRs telescope, gives us confidence in the astrophysical nature of the phenomenon detected: it is very probably a gamma-ray burst.

In order to alert the community, we drafted a circular summarising our detection, including the position needed to follow the phenomenon in optical. Initially, this position was provided solely by ECLAIRs, but after a few minutes we received a more precise location, obtained thanks to rapid observations with the MXT telescope on board SVOM. Our circular is published at 23:18 (T0+53 min): https://gcn.nasa.gov/circulars/39154. The burst was named GRB 250205A.

Meanwhile, the VT instrument is locating the source with an excellent accuracy of the order of one arcsecond (https://gcn.nasa.gov/circulars/39159). These observations confirm the transient nature of the phenomenon, as the luminosity is already starting to decrease. Time is running out to continue observations before it’s too late!

For the specialists on the ECLAIRs and MXT instruments observing at high energy, it’s time to go to sleep, but for the colleagues in charge of optical follow-up, it’s only the beginning. In the hours that followed, several ground-based observatories began observing the sky around the position provided by SVOM: the Observatoire de Haute-Provence (T193), the Roque de los Muchachos Observatory on the island of La Palma (LT, GTC), and the National Astronomical Observatory of San Pedro Mártir in Mexico (Colibri). Space telescopes are also observing the target (Swift, Einstein Probe).

These various optical and near-infrared observations also confirm the transient nature of the phenomenon, with the luminous flux diminishing rapidly over time.

Thanks to spectroscopic observations made at just T0+1h45 with the Large Telescope on the Canary Islands (10.4 m in diameter), the distance of the gamma-ray burst has even been determined. Its redshift is 3.55 (https://gcn.nasa.gov/circulars/39160), which means that the light emitted by this gamma-ray burst – which undoubtedly marked the birth of a black hole during the collapse of a very massive star – was emitted at a time when the Universe was only 1.8 billion years old. Its light travelled to us for almost 12 billion years before being detected by the instruments aboard SVOM!

There is still a lot of analytical work to be done to fully understand the precise nature of the phenomenon and to determine its characteristics, but we can already be delighted that the sequence of multi-wavelength observations, both onboard SVOM and on the ground within the community, has been carried out so quickly. This made it possible to observe the burst at several wavelengths and even to obtain its distance.

Contact : Andrea Saccardi

GRB 241001A: from the look of SVOM to the deep eye of JWST

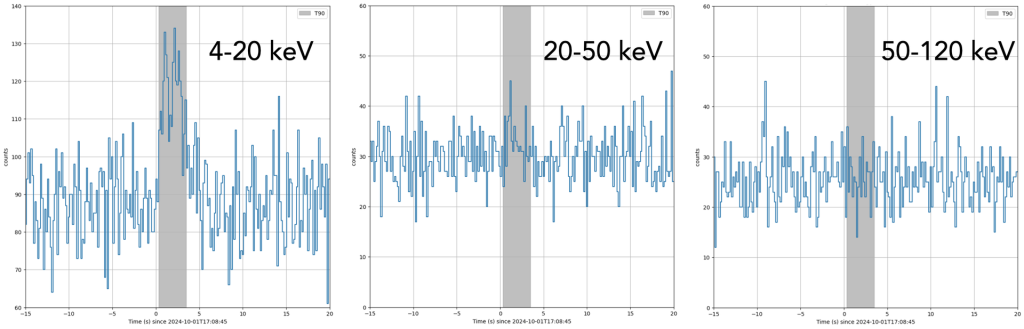

On 1 October 2024 at 17:08 UT, as SVOM continued its commissioning phase, a weak emission signal was detected by ECLAIRs: XRF 241001A (GCN37655). This gamma-ray burst had nothing of the flamboyant brilliance of the majority of its predecessors. It was an X-ray flash (XRF), a more discreet variant of the classic gamma-ray bursts. Identified in the early 2000s thanks to the BeppoSAX satellite, XRFs are an atypical subclass of GRBs. Their spectrum, dominated by X-rays rather than gamma rays, makes them more difficult to detect by the Swift or Fermi satellites, which are better suited to detecting gamma-ray bursts.

In search of the afterglow emission

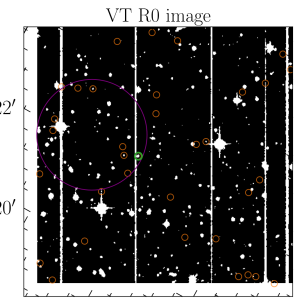

Shortly after the signal was detected, the SVOM and international multi-wavelength tracking system was activated. The SVOM teams immediately requested a rapid observation of the Swift satellite with its XRT instrument to detect the possible X-ray afterglow of the phenomenon. On Earth, the telescopes of the GRANDMA network and the Las Cumbres Observatory (LCO) quickly pointed their instruments at the source to obtain the first images of the optical counterpart and improve the location of the burst. (GCN37667, GCN37679).

Distance measurement

Unlike typical gamma-ray bursts, the afterglow of XRF 241001A was relatively modest, both in the X-ray and optical domains, and challenged one of the most powerful telescopes on the ground, the Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile. The VLT’s X-shooter instrument was able to capture a spectrum of the last moments of the optical counterpart in order to measure its distance. Although the signal in the spectrum appears weak, it is possible to distinguish both the absorption lines typical of matter swept along by the relativistic jet on the line of sight and the emission lines of the galaxy hosting the explosion. Both show the same distance with a redshift of z = 0.57, i.e. 5.6 billion years ago (GCN37677).

A supernova revealed by JWST and VT

The distance and atypical nature of this event aroused the interest of the community, including an international team of researchers who carried out observations with the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) to better understand its origin. On 24 October, 24 days after ECLAIRs detected the burst, a spectrum of the source was obtained with JWST’s NIRSpec instrument, revealing emission consistent with that of a type Ic-BL supernova (GCN37867). This type of supernova, particularly energetic with very broad spectral lines produced by ejecta at extreme speeds and frequently associated with gamma-ray bursts, results from the explosion of a massive star that has lost its outer envelope of hydrogen and helium before collapsing. At the same time, the VT has revisited the position of the burst on several occasions and has tracked the emergence of the supernova using imagery. The association of a supernova with this XRF reinforces the idea that at least some of these phenomena are indeed linked to the explosion of a massive star.

Exploring the origin of XRFs with ECLAIRs

However, XRF-type bursts are still poorly understood. Are they simply GRBs seen from a different angle? Or is it a physically distinct phenomenon, linked to less energetic jets or a brief luminous emission that occurs when the shock wave from a supernova pierces the star’s surface? The data collected on XRF 241001A provide a new anchor for better understanding this population of cosmic explosions. They also illustrate the ability of the ECLAIRs instrument to detect gamma-ray bursts that are spectrally softer and less energetic than those regularly observed by Swift or Fermi, offering a promising new perspective on these cosmic phenomena.

Contact: Benjamin Schneider

Switch-on of the ECLAIRs trigger and first detection of a gamma-ray burst

The first gamma-ray burst detected by the trigger system on board ECLAIRs is GRB 240713A. The event was observed on 13 July 2024, and arrived at just the right moment to take part in the fireworks celebrating France’s bank holidays.

On that Saturday, the SVOM satellite had just completed its third week in orbit, in the middle of the instrument commissioning phase. After its launch on 22 June 2024, a number of key milestones were successfully achieved, including the switch-on of the ECLAIRs onboard computer on 25 June, the switch-on of the ECLAIRs camera and the first data acquisitions.

The detection software on board ECLAIRs had just been activated on 11 July when the first gamma-ray burst was detected 2 days later. As the real-time alert messages sent to the VHF transmitter had not yet been activated, we found the alert information in the data received via the X-band at 5:22 am (French time) at the CEA in Saclay. When we woke up and decoded the files, we were surprised to find the very first alert sequence produced at 2:02 UTC.

For GRB 240703A the software produced a sequence of 6 alerts, 3 alerts from the CRT (Count-Rate Trigger) algorithm and 3 other alerts from the IMT (Image Trigger) algorithm1.

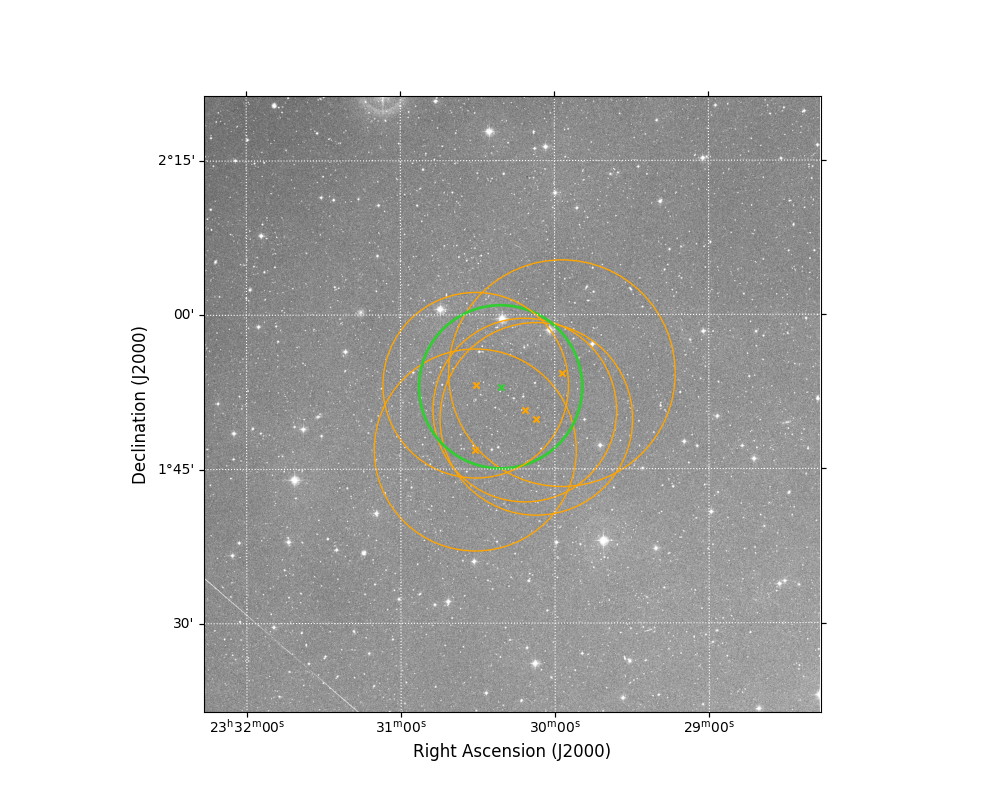

The alert with the best signal-to-noise ratio was produced by IMT, giving a location radius of 8.8 arcminutes around the position 352.59°, 1.88° in right ascension and declination in the celestial equatorial reference frame. The software also produced an image of the sky in which the presence of a point source is clearly visible.

Confident in this detection, we then distributed to the international community the first SVOM Circular entitled The first probable GRB Located on-Board SVOM by ECLAIRs.

Following our announcement, scientists at the GBM instrument on the Fermi satellite, whose trigger algorithm had not detected the event on board, searched their ground-based data archive and found a 32-second low-energy signal coinciding in time and originating from the same region of the sky as the ECLAIRs detection. Extensive follow-up resources were then deployed, including the Neil Gehrels Swift space observatory and the Einstein Probe mission, which pointed towards the position of ECLAIRs, as well as ground-based telescopes operating in the visible. However, most of these follow-up observations began more than a day after the event, so these searches were unable to locate the event more precisely on the sky.

This very first successful detection of a gamma-ray burst by ECLAIRs, validated by Fermi/GBM, qualifies SVOM’s triggering system, which just three weeks after its launch has demonstrated its excellent performance.

- CRT and IMT: these two algorithms complement each other and analyse the camera data independently and in parallel. IMT systematically reconstructs images of the sky every 20 seconds, by deconvolving the detector image using the coded mask, and then adds them together to construct images with exposure times ranging from 40 seconds to 20 minutes. CRT works on time slices ranging from 10 milliseconds to 20 seconds, first detecting an increase in count rate above a temporal model of the background noise, and for the best time slice found in excess, it then reconstructs the image of the sky. In all these reconstructed sky images, these two algorithms search for the presence of a point source that does not correspond to the position of a source listed in the catalogue of known sources, and produce an alert message for each of these detections. ↩︎

Successful launch of the SVOM satellite

On 22 June 2024 at 07:00 UTC the Long March 2-C rocket blasted off from its launch pad carrying the SVOM satellite into space.

A few minutes later, the satellite was separated from the launcher, and 40 seconds after separation, the solar panels were deployed.

During its 12th orbit, the payload computer was switched on and the parameters of the control and attitude system were adjusted. The VHF transmitter was switched on on 23 June during the 16th orbit and the first packets were received by the Tibet station in Lhasa.

The VT and GRM were powered up on 24 June. ECLAIRs and MXT were powered up on 25 June. The ECLAIRs camera was switched on on 1 July.

The first GRM burst was detected on 27 June.

ECLAIRs detected and located its first burst on 13 July.

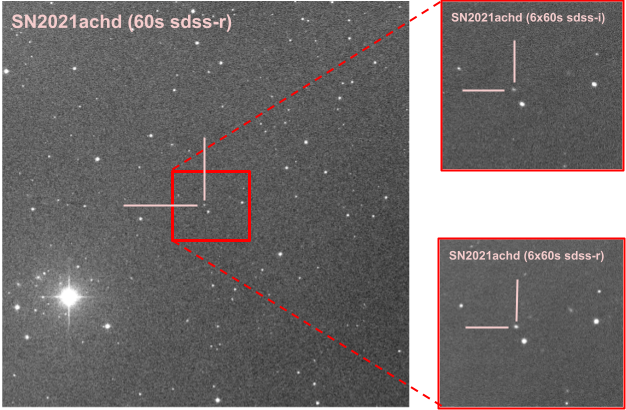

On 9 November 2021, the French Science Center (FSC) of the SVOM mission generated and sent its first alert to a ground-based robotic telescope for automatic photometric monitoring. This first test was carried out with the 50 cm robotic telescope IRiS (Initiation à la Recherche en Astronomie pour les Scolaires) located at the Observatoire de Haute Provence during a SVOM scientific meeting held there. The objective of this test was multiple:

- test the FSC’s alert generation and delivery system;

- test the real-time communication between the FSC and observers from outside the SVOM collaboration;

- ensure the proper transmission of SVOM alert information and optical tracking by ground-based robotic telescopes;

- analysing images taken in order to identify the transient source at the origin of the SVOM alert.

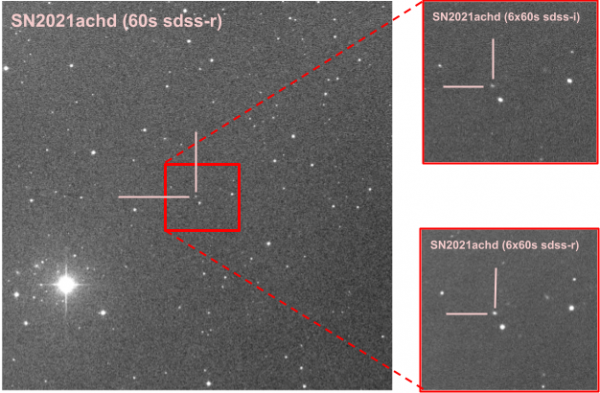

For this test, the FSC teams used the coordinates of a still relatively bright Type Ia supernova, SN2021achd/ZTF21aciwkzc (detected by the US ZTF optical survey on 7 November 2021), to simulate the position of a gamma-ray burst that would have been detected by the ECLAIRs instrument on board the SVOM satellite. On 27 October 2021 at 21:15 (local time), the FSC transmitted the alert to the IRiS telescope via a dedicated communication channel. Between the generation of the SVOM alert and its transmission to the IRiS telescope, only 1 to 2 seconds elapsed. It took a few more tens of seconds for the IRiS observation scheduling system to schedule the observation and point the telescope at the target to acquire the first follow-up image. In total, about 1 minute will have elapsed between the reception of the alert and the start of IRiS acquisitions. In total, a sequence of 79 images was taken during the rest of the night (60x5sec exposure with an sdss-r filter, then 9x60s in sdss-r and 10x60s in sdss-i). Each image taken by IRiS was stored in real time in a shared directory with the FSC, which was then able to analyse the images.

The precise analysis of the images is still underway, but supernova 2021achd was clearly detected in both the individual and cumulative images (see Figure 1).

In the context of the monitoring of a SVOM gamma-ray burst, the photometric analysis will make it possible to study the temporal behaviour of the optical transient source. This analysis will make it possible to identify whether the flux evolution of the transient source is in agreement with the expected light curve for a gamma-ray burst. The automation of this type of analysis is underway in order to be as reactive as possible as soon as IRiS images are taken.

This test was therefore conclusive in every way. It demonstrated the ability of the SVOM alert system to quickly deliver crucial information to the ground-based telescope teams in order to characterise the transient sources of interest as quickly as possible.

Further tests will take place in the coming months to collect more statistics on the stability of the SVOM alert system and to fine-tune the observing strategies. In parallel, real-time observations of gamma-ray burst alerts detected by the US Swift mission and redistributed by the FSC will also be scheduled in the coming months with SVOM partner telescopes.

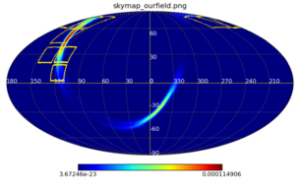

Optical follow-up of gravitionnal waves

The first results of the space mission SVOM (for Space-based multi-band astronomical Variable Objects Monitor) have just been released before the launch scheduled for the end of 2021. How is this possible? Quite simply because this ambitious Franco-Chinese mission, which aims at studying gamma-ray bursts of the Universe, is also developing a network of ground-based cameras able to detect the emission of visible light that follows the outbreak of these bursts, the most violent known explosions. This network, dubbed Ground-based Wide Angle Camera (GWAC), is already in operation at the Xinglong Observatory in Northeast Beijing (China). Its test version, named Mini-GWAC, successfully concluded a first campaign of monitoring and real-time follow-up of gravitational wave sources discovered by the LIGO (USA) and Virgo (Italy) facilities. These results are being published in the journal Research in Astronomy and Astrophysics.

See the luminous echo of a gravitational wave

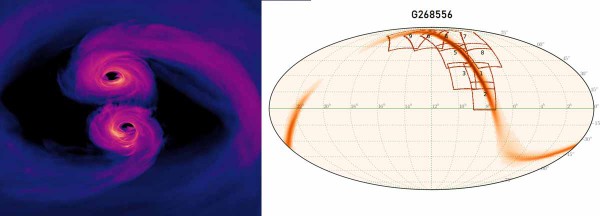

The SVOM team has just published the results obtained by the Mini-GWAC instrument of the follow-up of the second sequence of gravitational wave detection (run O2) by LIGO and Virgo that took place from November 2016 to August 2017. Not less than 14 potential events were published by LIGO in this interval, eight of which were monitored by Mini-GWAC. Other six events were subsequently retracted by LIGO.

For two of them, the most spectacular, GW170104 and GW170608 which have been confirmed as resulting from the fusion of two black holes, optical tracking has worked remarkably well. In the case of GW170104 (for Gravitational Wave of January 04, 2017), it is the result of the merging of two black holes of mass approximately 20 and 30 times that of the Sun.

Mini-GWAC was able to observe GW170104 a little more than 2 hours after the triggering of the alert and provide data for 10 hours, covering 62% of the error box. For GW170608 (June 8, 2018), nearly 20% of the region was covered. In both cases, no visible emission was detected, up to a magnitude of about mv = 12.

The final version of the GWAC installation that was commissioned in late 2017 at the Xinglong Observatory (China) is now able to track gravitational wave alerts down to a visible magnitude mv = 16, more than 40 times fainter than the test version. In some cases, the emission of gravitational waves is also accompanied by gamma-ray bursts that will also be detected by the other SVOM instruments [1]. The entire GWAC device is now ready and able to detect the visible counterparts of these events, even before the launch of the SVOM mission.

[1] SVOM is a Franco-Chinese mission for the observation of the gamma-ray bursts of the Universe. Its launch is currently scheduled for the end of 2021.

[2] GWAC is one of the components of the SVOM mission which also includes 4 instruments (ECLAIRs, MXT, GRM and VT) * which will be onboard the SVOM satellite. GWAC aims to complete observations from the ground to study and identify gamma-ray bursts detected from space by the SVOM satellite.

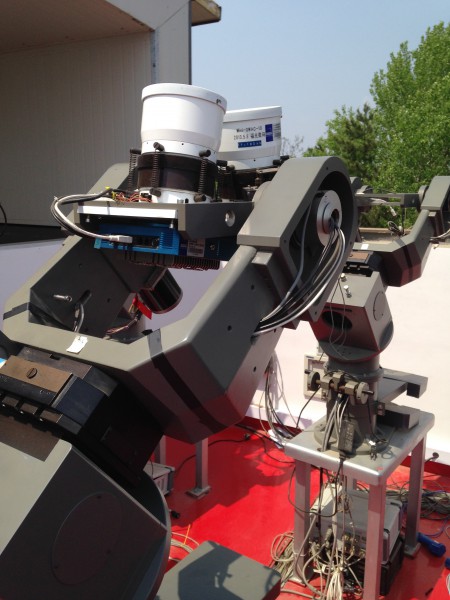

GWAC consists of 10 mounts each carrying 4 cameras of 18 cm in diameter and thus covering a total field of view of about 5000 square degrees. Each of the 40 cameras is equipped with a 4096 × 4096 E2V CCD operating in the 0.5 to 0.85 ?m wavelength band with a field of view (FoV) of 150 deg². GWAC provides source locations up to a visible magnitude mv = 16 with an accuracy of 11 arcsec (for a 10 s exposure).

The preliminary Mini-GWAC test version consisted of a system of six mounts, each equipped with two cameras (Canon 85 / f1.2).

Publication :

“The mini-GWAC optical follow-up of the gravitational wave alerts.

Results from the O2 campaign and prospects for the upcoming O3 run.”

D. Turpin et al., Research in Astron. Astrophys. 2019 (in press), see  the publication in (PDF)

the publication in (PDF)

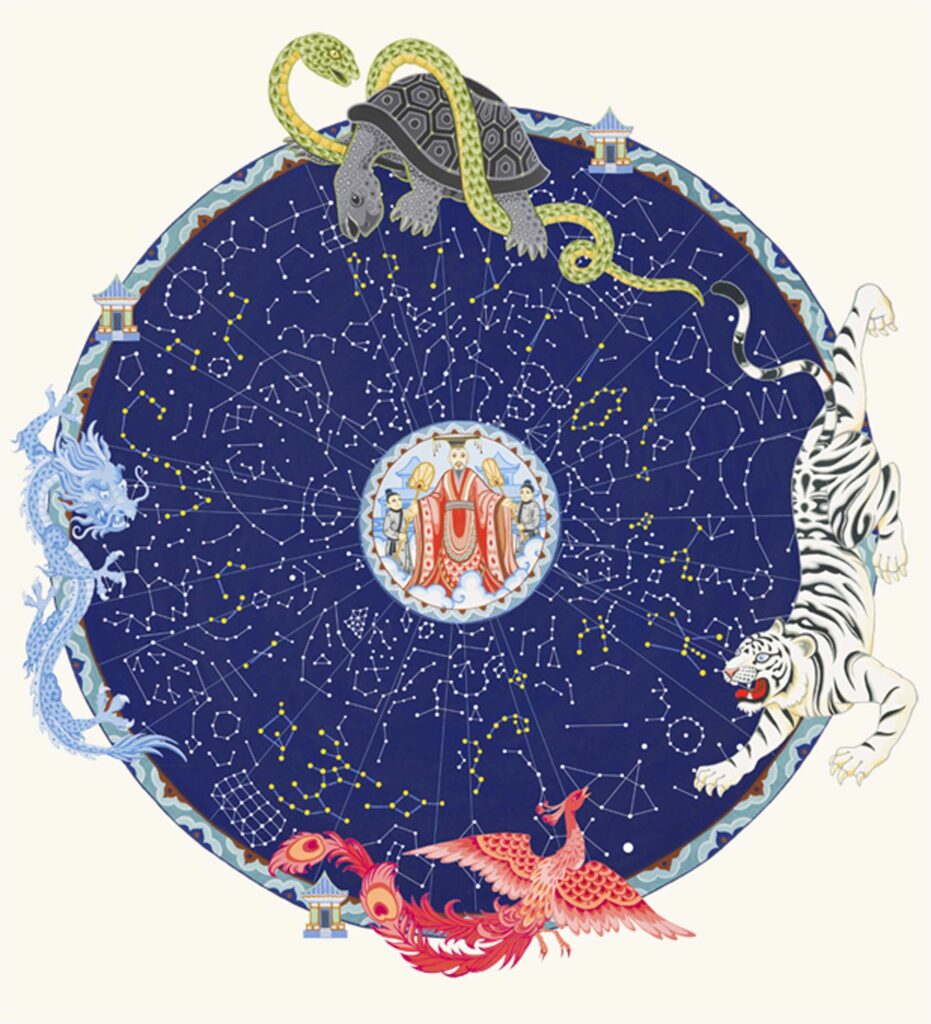

The combination of two worldviews

In the past, Europe and China have had two radically different visions of the cosmos. While the former has long thought of the fixed and immutable sky as revealing only silent perfection, the latter has, on the contrary, relentlessly tracked down the slightest celestial changes, sometimes almost imperceptible phenomena, betrayed only by infinitesimal manifestations. Unchanging sky or transient sky therefore remained for a long time two opposing visions. Today the transient sky has become an irreplaceable source of information for astrophysicists and China and Europe are joining forces to unlock the secrets of this constantly changing world where some cataclysms can occur in just a few fractions of a second.

The SVOM (Space-based multi-band Variable Objects Monitor) space mission, to be launched in 2021, will be the second Sino-French scientific mission from space after the launch of CFOSAT (China-France Oceanography SATellite) on 29 October 2018. Its purpose is to detect the brutal sudden end of the very first stars, located at the edge of the Universe, and also to help locate super-powerful cosmic phenomena generated by the fusion of compact stars. This is an undeniable tribute to the long Chinese tradition.

Unchanging sky and transient sky

Europe, and more broadly the Mediterranean basin, has mainly received its astronomical tradition from the ancient Greek world. From an often very limited and superficial observation of the heavens, the ancient Greek thinkers had imagined a cosmic world divided into two distinct domains. On the one hand, the sub-lunar world close to the Earth where all the changing cosmic phenomena (meteors, comets,…) were confined and on the other hand the supra-lunar world where the errant bodies that are the planets orbit in perfect circles. This world itself was entirely contained in a last celestial sphere, the fixed, immutable and eternal sphere that carried the stars. In this highly idealized vision, it was therefore impossible to think of discovering any change whatsoever in this last starred sphere, which, according to common experience, indeed seemed largely untroubled.

After the collapse of classical Greek culture at the beginning of the modern era, this same idealized vision was taken up by the two monotheistic religions, Christianity and Islam, which were to develop in turn. This time, the perfect and immutable character of the heavens was no longer a aesthetic vision from philosophical thinkers, but became a strict religious prescription that sought to describe the perfection of the great Creator. To identify elements that could question this cosmic perfection then became a frontal opposition to the religious powers that also dominated the political world of the time. This religious dogma has thus acted for nearly 1500 years on astronomical science in Europe.

In contrast, other parts of the world have not been subjected to this religious censorship, and in the case of China, on the contrary, it was the political power itself that has favoured since the dawn of time, the deep examination of the changing sky, permanently scanning the heavens in search of transitional phenomena.

In a premonitory way, China is the civilization that has given the most importance to the changes in the skies. At the origin of this quest, the permanent concern to preserve the harmony between Earth and Heaven. The two terrestrial and celestial worlds were seen as two complementary worlds in constant interaction and any disruption of balance in the sky heralded a similar disruption on Earth that needed to be identified. In this vision of Heaven as a mirror of the Earth, the main role was assigned to the sovereign himself, called “Son of Heaven” (Tianzi), because his essential responsibility was to guarantee this Earth-Sky harmony. The Chinese emperor did not receive his mandate and legitimacy from a simple family line or even a conquest, but above all he had to justify a “celestial mandate” (Tianming) granted to him if he could predict and anticipate astronomical phenomena. In this sense, China is the only country in the world to have elevated astronomy to the rank of state science.

On the orders of the emperor and the central power, everything that could disturb the harmony of the heavens was hunted down, discovered and interpreted. Entire bodies of astronomers and astrologers were mobilized night after night in imperial astronomical observatories gathering hundreds of people (observers, timekeepers and clepsydra, calendar specialists, mathematicians,…) who had nothing to envy our great modern scientific institutes.

From the beginning of the Hans, in the second century BC, the specifications were clearly established and reported to us by the great historian-astronomer of ancient China, Sima Qian, in his encyclopedic work “The Historical Memories”: “If in the whole cycle from beginning to end and from antiquity to modern times the changes that occur at fixed times have been observed deeply and if we have examined their details and the whole, then the science of the Governors of Heaven is complete. “Shiji, Historical Memoirs of Astronomer Historian Sima Qian (109 to 91 BCE).

This perfect organization, which has covered more than forty centuries of Chinese civilization, has provided the world with fundamental astronomical discoveries, often still greatly underestimated.

The existence of sunspots on the Sun’s surface was thus clearly established as early as the Hans dynasty (206 BCE to 220 CE) while their discovery in Europe is attributed to Galileo (1613 CE). Even more spectacularly, the first mention of a star explosion, resulting in the temporary appearance of a new star (novae or supernovae), seems to have been documented in China as early as the 15th century BC and precise catalogues and reports of these spectacular events are available since the Han period. In Europe, the first description of such phenomena was given only by the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe in 1573.

It reads (from top to bottom and from right to left, highlighted in red): “In the first year of the Jiayou reign, in the third lunar month[from 19 March to 17 April 1056], the head of the Astronomy Bureau said: “The invited star has disappeared, which is a sign of the host’s departure.” Earlier, during the 5th month of the first year of the Zhihe reign[July 1054], this star had appeared in the East, guarding Tianguan[??- the star ? Tauri]. She was visible during the day as Venus. It pointed its rays in all directions and its color was pale red. It remained visible[during the day] for 23 days. ». Crab supernova remanent, X-ray image composition, visible and infrared light. Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/SAO/F.Seward; Optical: NASA/ESA/ASU/ASU/J.Hester & A.Loll; Infrared: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Univ. Minn./R.Gehrz.

Thus the appearance of a supernovae, a new transitional star, reveals an event that is crucial to the history of the universe: the explosion of a massive star that will spread in space all the complex cosmic elements (carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, etc.) produced in the star’s heart that can contribute later to the emergence of life on a planet.

In other areas of light such as gamma rays, the appearance of very short bursts of gamma radiation also marks the end of life of very large stars, which can be detected thanks to this signal up to the far limits of the Universe.

Finally, beyond light itself, the very structure of space-time can be transiently altered by the monstrous fusion of black holes or compact stars and reach us as gravitational waves, new messengers now detectable on Earth by laser-based sensors. In short, we are learning much more today from the transient sky than from the permanent sky

All these transient phenomena are the main objectives of the Franco-Chinese SVOM mission. Their detection, location and precise description will be recorded to better interpret the sky, just as the astronomers of the Han dynasty did more than 2000 years ago. Thus the same concern to better read the changes in Heaven, a quest shared today by China and France thanks to SVOM, is renewed centuries later.

References

Jean-Marc Bonnet-Bidaud, « 4000 ans d’astronomie chinoise », Ed. Belin, 2017.

Joseph Needham and Wang Ling. « Science and Civilisation in China, vol. 3, Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth », Cambridge University Press, 1959.

Xiaochun Sun and Jacob Kistemaker, « The Chinese Sky during the Han – Constellating Stars & Society », Ed. Brill, 1997.

Zezong Xi, Shuren Bo, « Ancient Oriental Records of Novae and Supernovæ », Science, vol. 154, p. 597, 1965.

The third SVOM scientific workshop, entitled “Disentangling the merging Universe with SVOM” and bringing together 70 participants, was held from 14 to 18 May 2018 at the Houches physics school in the Chamonix valley. This year, a scientific theme was particularly highlighted, the contribution of the SVOM mission to the study of gravitational waves at the dawn of the next decade. The observation strategy during a gravitational wave warning was at the heart of the debates.

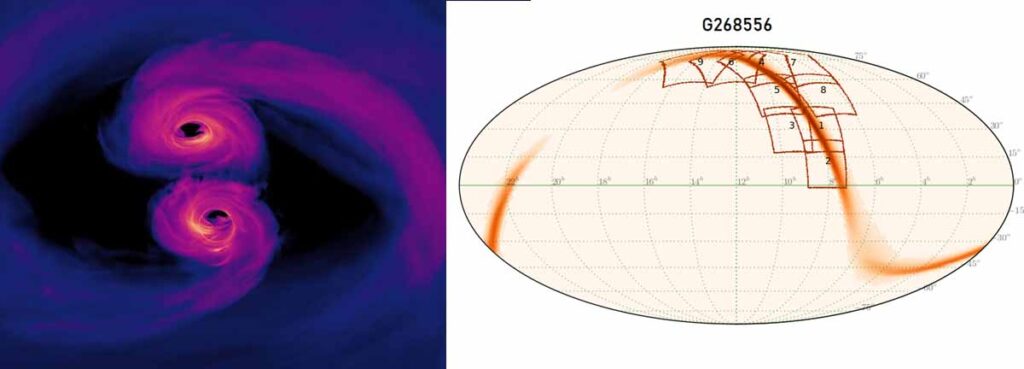

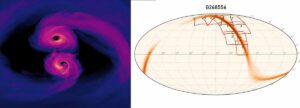

On August 17, 2017 the Ligo-Virgo collaboration detected a packet of gravitational waves from the fusion of two neutron stars lurking in the galaxy NGC 4993. Less than two seconds later, the Gamma ray Burst Monitor (GBM) of the Fermi mission detected for the first time an electromagnetic counterpart to this event, a signal confirmed by the Integral satellite. This correlated detection in gravitational waves and electromagnetic waves is a major scientific fact of the last decade. The SVOM mission, whose primary objective is the detection and study of gamma-ray bursts, is particularly well suited to contribute to this major scientific theme in view of its array of instruments equipping its space platform and the ground resources at its disposal.

During this workshop, several sessions described the state of the art of gravitational wave detection by active detectors, in terms of scientific results and future projections. The event of 17 August 2017 (fusion of two neutron stars) was the subject of special attention. The potential of the SVOM mission was highlighted, informed by simulations of the detection of such an event by the mission instruments and their contribution to the community.

Beyond this theme, the scientists exchanged on the more practical aspects of the technical constraints of the mission (orbit, accessible sky zone in accordance with the main program, opportunity and limit of modification of the satellite point linked to an alert, etc.).

The participants also took advantage of the majestic setting of the Houches School of Physics to address new research themes and update and complete the scientific document describing the mission in a broad sense (the White Paper).

The event of August 2017

On August 17, 2017, ground-based gravitational wave detectors (LIGO and Virgo) detected an event, called GW 170817, interpreted as the fusion of two neutron stars. This is the first time that LIGO detects a signal whose profile is similar to the fusion of two neutron stars, but what made the event even more unique is the temporal and spatial coincident detection of a short gamma burst GRB170817A by the GBM detector onboard the Fermi satellite. The detection was confirmed and announced in the following minutes by the SPI spectrometer onboard the INTEGRAL satellite.

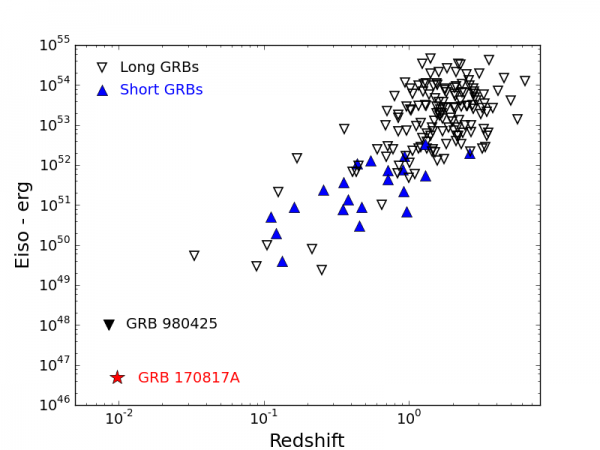

The characteristics of GRB170817A were published after a few hours on the site of the Fermi / GBM mission. This is a low-intensity short gamma burst lasting about 2 seconds. Taking into account the distance estimated by the gravitational wave analyses, as well as its observed flux, GRB 170817A is an unusual burst, particularly sub-luminous (see Figure 1). It could be a gamma burst seen from the side.

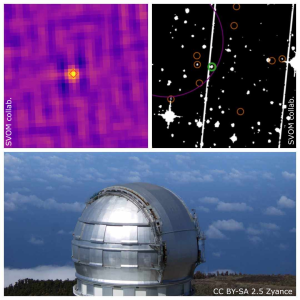

An unprecedented observational campaign followed, mobilizing dozens of observatories on Earth and in space to detect and characterize the electromagnetic counterpart of the gravitational wave source. Thanks to the contribution of Virgo, the error circle was considerably reduced which allowed a fast tracking on the ground by small telescopes. By selecting galaxies located at the distance deduced from the gravitational signal, the 1 m Swope telescope at the Las Campanas observatory detected a new source SSS17A near the galaxy NGC 4993 at 40 Mpc. In the hours that followed other telescopes (DLT 40, Vista, Master, DECam, LCOGT) confirmed this detection, motivating the whole community to focus on SSS17A and leading to the detection of the electromagnetic counterpart of GW 170817 in all the wavelengths of the ultraviolet to the radio domain. This unprecedented campaign was rewarded by the discovery of a kilonova [1].

The succession of observations that have made the detection and localisation of the electromagnetic counterparts of GW 170817 possible reinforces the observational strategy chosen for the SVOM mission. With its set of interconnected multi-wavelength detectors, covering the electromagnetic spectrum from gamma rays to infra-red, SVOM will be able to detect and study these gravitational wave sources resulting from the fusion of two neutron stars and producing short bursts.

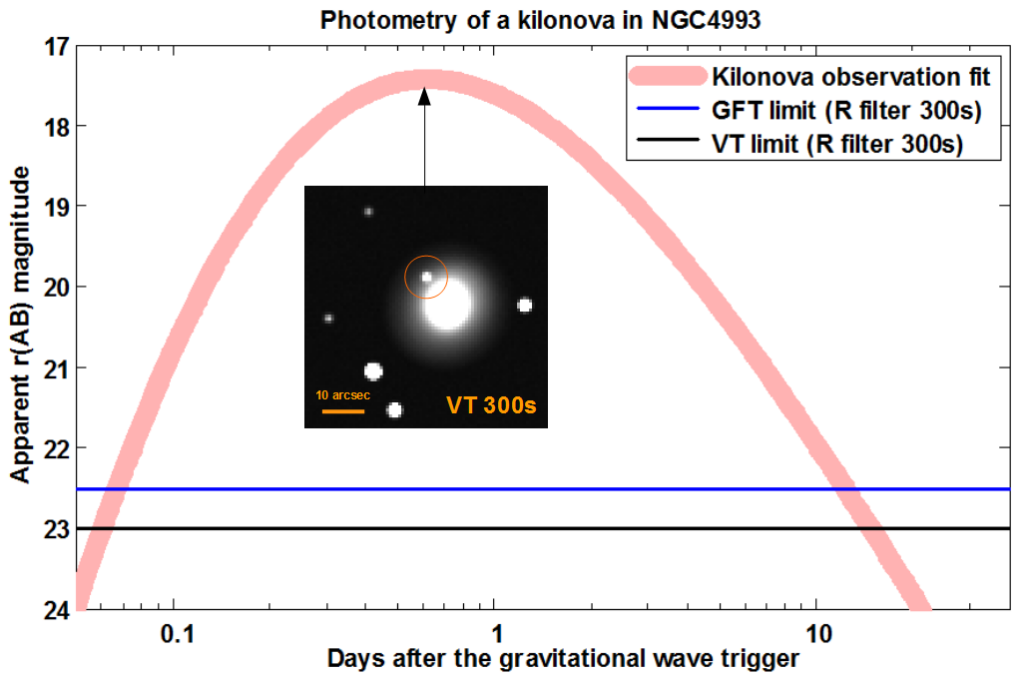

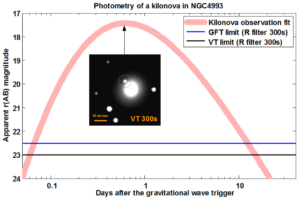

What would have SVOM seen if the mission had been online on the 17th of August 2017 ?

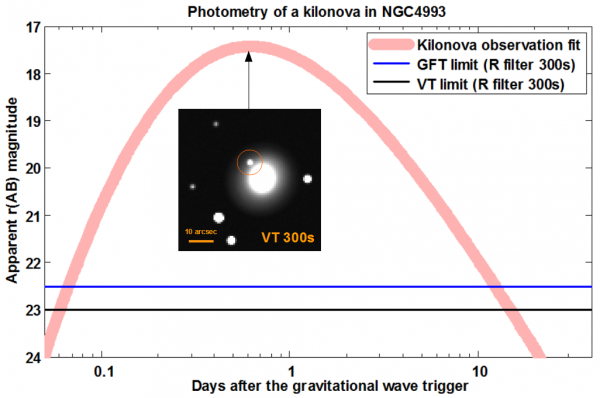

If the burst had appeared in the field of view of its high-energy detectors (ECLAIRs and GRM), SVOM would have detected it with a high probability and would have sent a trigger warning to the ground (see figure 2), all the while measuring the energy emitted in gamma rays. At the same time, the satellite would have slewed automatically to put the burst in the center of the field of view of its X-ray and optical instruments (MXT and VT), initiating an observing sequence of several hours. The optical counterpart of GW 170817, the emission produced by the kilonova associated with the fusion of the two neutron stars, would have been easily detected by the visible telescope VT [2] (see Figure 3).

But what would SVOM have seen if GRB170817A had not been in the field of view of its high-energy instruments (ECLAIRs and GRM) ?

Upon receiving the LIGO-Virgo alert at the French scientific center, SVOM would have triggered its robotic telescopes (F-GFT and C-GFT). By selecting nearby galaxies compatible with the probable distance from the event and contained in the gravitational wave detector error circle, SVOM’s robotic telescopes would have started a systematic search for the optical counterpart by performing several observation cycles. This strategy is particularly suited for the discovery of transient objects in their brightening phase. Thanks to its sensitivity but also thanks to its infra-red capabilities, the French GFT would certainly have detected the kilonova associated with GW 170817 (see figure 3).

In parallel, the French scientific center would have prepared a request for a multi-messenger opportunity target, asking the satellite to interrupt its observing sequence and point at various regions of the sky within the error circle of the gravitational wave detectors. It typically takes about ten hours to reprogram the satellite. Although arriving later, the VT would have easily detected the kilonova associated with the fusion of the two neutron stars (see Figure 3).

And now ?

In the beginning of the next decade, thanks to its ground and space-based instruments, the SVOM mission will certainly be a major player in the study of the transient sky and should significantly contribute to the study of gravitational wave sources. Starting next year, some of the SVOM ground-based telescopes (GWAC) should be operational and should validate the strategies implemented within the consortium at the next LIGO-Virgo data collection scheduled for autumn 2018.

[1] Kilonova: during the coalescence of two neutron stars, neutron-rich material is suddenly released under temperature and density conditions very favorable for the nucleosynthesis of heavy elements by the fast neutron capture process (process r). This is expected to result in the quasi-isotropic ejection of heavy-element-enriched material. This material is heated by the radioactivity of freshly synthesised elements and radiate thermally, with a color evolution from blue to red due to progressive cooling. This emission called kilonova has a physical origin quite distinct from the gamma ray burst and its afterglow.

[2] For this event no short-term X-ray observations occurred. It is therefore difficult to predict a possible detection by the MXT X-ray telescope, despite the fact that it is expected by various models.

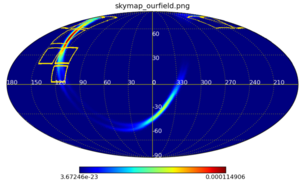

The third gravitational wave event (GW170104) discovered by the LIGO-Virgo collaboration confirms the existence of massive stellar black holes with a mass larger than 20 solar masses. These two in-orbit stellar masses stars finally merged to form a compact object of nearly 50 solar masses. During this process, a huge amount of gravitational wave, predicted by the general relativity theory, is emitted. This is precisely the signal of this fusion that the two LIGO interferometers detected on earth for the third time.

Searching for an electromagnetic counterpart to such event is today a challenge, both on a observational side or on a theoretical aspect. Many multi-wavelength networks, on ground and in space, share this goal. Among them, the SVOM mission has started to survey the GW candidates with a dedicated instrument, the SVOM/mini-GWAC equipment, pathfinder towards a more complete SVOM instrument. Starting just a few hours after the communication to the scientific community of the GW position, the following text describes the different steps of this search.

GW170104

The gravitational wave event GW170104 has been detected on 4 January 2017 at 10:11:58 UTC by the LIGO-Virgo consortium with the twin advanced interferometers Hanford and Livingston located in the United States.

This event is the result of the coalescence of a pair of stellar-mass black holes with respectively 31.2(+8.4;?6.0) and 19.4 (+5.3;?5.9) solar masses. The source luminosity distance is 880 (+450;?390)??Mpc corresponding to a redshift of z=0.18 (+0.08;?0.07). The signal was measured with a signal-to-noise ratio of 13 and a false alarm rate less than 1 in 70?000 years.

Timeline and Localization error box

The GW alert has been delivered to the astronomical community with a delay of 6.3 h.

The initial 90% localization error box covers an area on the sky of 2065 deg2.

An update of the localization error box has been delivered 4 months later with a 22% reduction of the localization error box.

SVOM activity

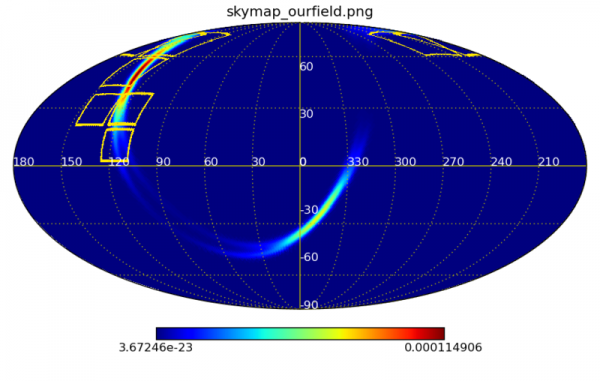

As soon as the GW alert was delivered to the astronomical community (6h after the trigger time e.g 4 hours after the beginning of the Chinese night), the probability skymap was quickly digested in order to produce the follow-up observation plan.

The mini-GWAC telescopes covered 80% of the error box in 14exposures of variable duration between 1 and 3 hours.

The SVOM group reported their follow-up observations in a circular published at the end of the night.

SVOM/Mini-GWAC follow-up observations were unique in the optical band: SVOM/mini-GWAC performed the largest probability coverage of GW170401 localization in shortest latency for optical band.

At this time, we didn’t detect a relevant electromagnetic counterpart but for the future, we look forward the whole GWAC system (limit mag 16), in operation at fall 2017.

SVOM science is on the way !

After the one holds in Les Houches in April 2016, the second scientific workshop of SVOM mission took place from 24 to 28 April 2017 at Qiannan inside the province of Guizhou located in the south of China. Called Surveying the Fast Changing Multi-wavelength Sky with SVOM”, this meeting gathered almost 90 participants on a site near the new giant radio telescope FAST.

The new generation of observatory instruments accessible today for the scientific community allow a sky survey, not only for all the color or wavelength but also for non-photonic windows with neutrinos or gravitational waves. The abundance and the quality of observatory tools in space as well as on the ground put this astrophysics, called multi-messenger astrophysics, in a golden age. It provides access to information on the physics of emitter object but also explore the Universe until considerable distances, opening opportunities towards cosmological studies.

Within this context, several main topics were covered throughout the workshop: gamma ray-burst (type of progenitor, cosmological probe), gravitational waves (formation of massive stellar black holes and their evolution over the universe history), neutrinos (type of sources, link with gamma ray-burst and high energy cosmic rays) and fast radio burst FRB (mechanisms involved, survey of intergalactic medium).

At each stage, theoretical and observational talks allow to review the state of the art and to trigger scientific debates. The role of SVOM in this scientific overview was the core of several scientific sessions.

During this workshop, a visit of the giant telescope FAST inaugurated in September 2016 was planned.

Located in a region with particular landscape, this instrument is the jewel of the Chinese radio astronomy.

The schedule and the presentation of this workshop are accessible here.

The next workshop will be held in France from 13 to 18 May 2018 in the Ecole de Physique des Houches located in Chamonix valley.

As part of the preparation of SVOM mission, a scientific workshop from 10 to 15 April 2016 at Ecole de Physique des Houches in the Chamonix valley, called « The Deep and Transient Universe in the SVOM Era: New Challenges and Opportunities ».

This workshop aimed to gather the scientific community (Chinese and French) interested in the project. Although the study of gamma ray burst remains a main goal of the mission, the time dedicated to targets of opportunity will grow up like we noticed for the Swift mission. And thus, SVOM is also a multi wavelength mission devoted to the study of the transient sky. The subjects discussed were very diverse: gamma ray burst, Galactic X-ray binary, active galactic nuclei or even the distant Universe. Research of messengers that are non-photonic like gravitational waves or neutrinos were also discussed during the workshop.

It also allowed the participants to put the bases of a white paper. This document is going to be presented during the end-of-phase B review, which will take place in China in July 2016. It will provide a work basis to the scientific community interested in the SVOM mission. Gathering more than 70 participants, mostly Chinese and French, the workshop was an opportunity to develop contacts and dialogues in the country setting of the Ecole de Physique des Houches.

The schedule and the presentations of the workshop are available here.

This meeting was the first one of a series of yearly appointment open to the community. The next one is planned in April/May 2017 in the province of Guizhou in China near the giant radio telescope FAST presently under construction.

Consult the white paper prepared following this workshop: The Deep and Transient Universe in the SVOM Era: New Challenges and Opportunities – Scientific prospects of the SVOM mission (2016 edition)